Magic and Meaning: Conjuring the World of Spellslinger by Sebastien de Castell

"Magic for me is as much about politics and identity as it is about fireballs and wind spirits."

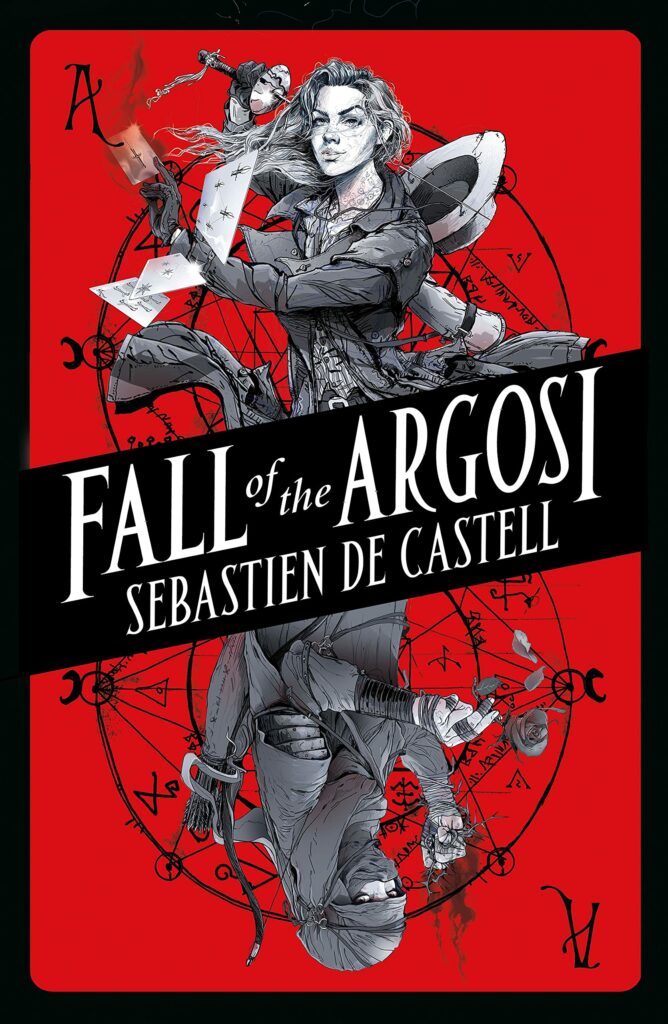

This post was written by Sebastien de Castell, author of Fall of the Argosi and is sponsored by Hot Key Books.

With the success of the Spellslinger series, I’m often asked how I go about building a magic system for my fantasy worlds. I always find this a tricky question to answer and one that’s become more complicated by a fan culture that sometimes treats books as things to be analyzed, categorized, and debated rather than simply read and enjoyed. We talk about hard magic and soft magic these days, and whether a book does or doesn’t follow Sanderson’s Laws (I’ve met Brandon Sanderson; he’s a lovely person and a hugely popular author, but I don’t think he expects other authors to be governed by his writing rules). In an age obsessed with intertextuality, spells in novels get examined in terms of how closely they hew to those in Harry Potter or Dungeons & Dragons or the latest open world video game. When I’m working on a new fantasy series, I’m sometimes queried early in the process as to how easily the magic system I’m devising might be adapted to a role playing game in future.

I don’t begrudge anyone their joy in comparing and contrasting magic systems or even wanting fantasy novels to be the launching off point for movies and video games. But for me as an author, those concerns don’t have much connection to the process by which I create a magic system. Magic for me is as much about politics and identity as it is about fireballs and wind spirits. In our own world, magical traditions are cultural artifacts that reflect the societies in which they emerged. Beliefs about magic reveal to us what people saw as wondrous or terrifying, beneficent or baleful. Not only that, but often our definition of “evil” magic is simply whatever mysticism is practiced by people who don’t look or act like we do. In that sense, creating a magic system is about designing not only a series of connected symbols, spells, and rituals, but asking what those mystical beliefs tell you about the fictional society in which they emerge.

View this post on Instagram

The Jan’Tep: Magic as Meritocracy

In the Spellslinger series, the Jan’Tep are a culture devoted to magic. They see spells and the ability to cast them as not only a kind of science but as having a moral dimension: those most skilled at using magic are more intelligent, more disciplined in their minds, more pure in their thoughts and intentions. Magic is seen by the Jan’Tep as a meritocracy, the way money and fame are in much of our own world. Among the Jan’Tep there are seven fundamental forms of magic: iron, ember, breath, blood, sand, silk, and shadow. When a young initiate manages to spark one of the metallic ink tattooed bands around their forearms, the thrill they feel isn’t only about proving they can wield magic, but that it also proves they’re clever and strong-willed and brave. It shows they are good. And as for all those others who can’t wield magic and are thus consigned to being the clerks, cooks, and servants of their society? Well, clearly that’s their natural purpose in life, otherwise they, too, would have sparked their tattooed bands.

The Whisperers: Magic as Morality

When I wrote the sequel to Spellslinger, Shadowblack, I wanted to explore other types of magic systems, and other beliefs about the nature of magic and what it tells us about ourselves. Whisper Magic, unlike the pseudo-scientific system of the Jan’Tep, is all about supplication. It’s about asking the wide range of spirits all around us – the Sasutzei of wind, the Zuhatzei in the trees, the Trumotzei who live in thunder, and all the others – for help. Unlike a Jan’Tep mage who seeks to dominate the fundamental forces of magic, a whisper mage has no fixed spells, but must learn to whisper their need, every syllable an emotional plea, so that a spirit might aid them, perhaps coming to live inside one of their eyes and showing them secrets unseen by those too arrogant to pay attention. To a Jan’Tep lord magus, a whisper mage is a kind of beggar, too weak to work proper magic. To a whisper mage, a Jan’Tep is a blind, deaf bully who bludgeons their way through the world, always heading to their own doom.

The Coin Dancers: Magic as Outlaw Folklore

The Gitabrians in Charmcaster, the third book in the Spellslinger series, have a different form of magic that aligns more naturally with their reliance on trade, exploration and mercantilism. The Castradazi coin dancers are viewed neither great leaders nor mystical hermits, but as roguish folk heroes. It takes tremendous dexterity to flip a sotocastra, sometimes called a Warden’s Coin, to make it open a lock, or spin an orocastra – a seeker’s coin – so that it will lead you towards gold or other valuables. Thus in a society where mercantilism and modernity are at the pinnacle of the social construct, magic becomes a kind of relic, neither especially prized nor feared, but relegated to the fringes.

The Shadowblack: Magic as the Inheritance of Evil

The magic of those branded as shadowblacks is terrifying and mysterious to those not born with the twisting black markings around one eye or the fingers or appearing as ebony teardrops on one’s cheeks. How could such a thing exist unless those possessed of it – or their parents – committed some horrible atrocity for which they must be punished? Whether these shadow mages manifest as Alacratists and Praemandors, Imperiasters and Lamentarists, to be blessed – or cursed – with the ability to wield shadowy forces that no one understands makes it easy to persecute those afflicted as demonic, and provides an excellent political basis for outcasting or even killing them.

The Argosi: the Magic of Humanity

The more I devised and wrote these various systems of magic, with all their attendant rules, names, and the physical laws behind them, the more I found myself craving something different – something I hadn’t seen much of in fantasy novels. I wanted a form of magic that wasn’t magic at all. I wanted something that reminded readers, and perhaps myself, that the vast inheritance of our own humanity is as wondrous as any spell.

In a world like that of Spellslinger, where there are so many different forms of magic and mages happy to wield their powers either for their own selfish purposes or for the advancement of their peoples at the expense of others, who stands up for all those who don’t cast spells? Who can stand up to a Jan’Tep mage or Shadowblack Imperiaster, unafraid of facing off against them with nothing but those abilities that we all possess to varying degrees? These were the questions that made me create the Argosi.

Have you ever found yourself mesmerized – absolutely entranced – by a live band? Or teared up at the beauty of a dance? Found your opinion of something entirely changed by a speech so perfectly and passionately delivered that it’s like being woken from a trance? What about watching the incredible way a martial artist can move, turning an opponent’s strength against them? Or how someone clever enough, with the right training, can notice something crucial the rest of us miss? Or my favourite of all: seeing someone with no chance of victory laughing in the face of certain failure and leaping off that cliff anyway. Put all these very human qualities and pursuits together, and you get the Argosi.

I decided to make them wandering philosopher gamblers, each following their own unique path. I wanted them to navigate the complexities of the world with four cardinal ways: the Way of Water, the Way of Wind, the Way of Thunder, and the Way of Stone. Whenever faced with conflict, and Argosi chooses which of those four ways should guide them, and takes responsibility for the consequences of their decision. They survive by drawing on the Seven Talents: defence, eloquence, perception, persuasion, strategy, resilience, and my favourite of all: swagger. They have elaborate names for these talents, like arta valar and arta loquit, but each one is a basic human ability or pursuit, developed and refined over a lifetime, turned into something that’s not magic and yet seems entirely magical when you witness it in action.

I mentioned earlier that magical traditions both in our societies and those of our fantasy worlds is inescapably political. Where we derive power and how we wield it is, in many ways, the very essence of politics. That’s why, of all the systems of magic I’ve created for my books, my favourite will always be that of the Argosi. That’s because it’s a magic that’s rooted in the idea that the most potent sources of wonder we’ll ever find don’t come from the supernatural at all, but from those very strange, very beautiful, very human talents that are available to all of us.

Get your copy of Fall of the Argosi, book 0.5 in the Spellslinger series, by Sebastien de Castell here.

Get your copy of Fall of the Argosi, book 0.5 in the Spellslinger series, by Sebastien de Castell here.