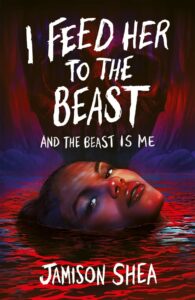

Jamison Shea on monsters and their debut novel, I Feed Her to the Beast and the Beast is Me

"Monsters feel like home for me, and many others, because they are extreme forms of catharsis, but the feeling isn’t limited to monsters."

This post was written by Jamison Shea, author of I Feed Her to the Beast and the Beast is Me.

MONSTERS FEEL LIKE HOME by Jamison Shea

Surrounded by violent trickster fae, Jude Duarte in The Cruel Prince by Holly Black decides that if she cannot be like them, she will be worse. The most exhilarating of her actions to me was not the espionage or even the murder, but the mithridatism. She poisons herself intentionally, progressively, to make herself immune, so that her enemy may never use her body against her again. It’s an unreasonable response to a reasonable fear. It is abhorrent, dangerous, a willful transgression against the self: she’s a monster.

And isn’t that what makes monsters so great? These dangerous, aggressive, abhorrent things that can go to “unreasonable” lengths and eat whatever they want and roar with abandon. People fear and revere monsters. We build our myths and religions around monsters. They’re transgressive.

In season 3, episode 21 of the original Charmed, “Look Who’s Barking,” Phoebe Halliwell, played by Alyssa Milano, is turned into a banshee. (Note: These are not the Banshees of legends. In the show, they are demons that feed on suffering.) Following betrayal by the man she loved, she is so heartbroken that the destructive screams of a banshee do not kill her—they transform her. She awakens with claws and sharp teeth and a hunger for pain. Pre-teen me, caked in eyeliner and loathing, saw this and thought, “Mood.”

It wasn’t the lore about witches or even the fake lore about banshees that fascinated me, that made me write story after story after story about monsters. Sure, the teeth and claws were cool, but it wasn’t entirely that either. It was the response to heartbreak that redefined what it meant to be sensitive. It was reimagining what it meant to feel sharply and respond to those feelings as a transgression. Phoebe as a banshee, Jude with her blackened fingernails, Medusa, Carmilla, Lady Rokujo in The Tales of Genji, Sadako from The Ring, Carrie, Red from Us, Sam Carpenter from Scream VI, Aaliyah as Queen Akasha in Queen of the Damned, even Hannibal Lecter (I’m sorry, I can’t help myself)—they’re all like superheroes for the melancholic. Their hunger gets reshaped by darkness instead of gamma rays or spider bites.

Then multiple people compared my novel, I Feed Her to the Beast and the Beast is Me, to the movie Pearl (2022).

I Feed Her to the Beast is about Laure, the only Black ballerina at a Paris academy, who strikes a deal with an eldritch god for the power to best her competition. And for anyone who hasn’t seen it (I only just watched it this week), Pearl is a prequel film starring Mia Goth. You might have seen the image still of a girl in a red dress wailing, “I’M A STAAAAAAAR!” The villain origin story follows the titular young woman working on her family’s farm and tending to her disabled father during the 1918 pandemic while her husband is off at war.

View this post on Instagram

Laure has a cosmic power as her weapon. Pearl wields a pitchfork and axe. Both girls dream of dancing. Neither girl gets what she wants in the end, not exactly.

I enjoyed Pearl and understand why people compared them. There is a heavy yearning for more than the life you’re given, the desire to be more than who you are now. There’s the element of class: in the famous, gilded opera house, Laure competes against her wealthy best friend who has influential parents, and Pearl, whose family farm can’t afford help, is up against her sister-in-law with a fur coat and no responsibilities. In a way, they both grapple with maternal pressure too—Pearl’s mother wants her to stop dreaming and do what’s expected of her, and Laure wants to be a star to prove the mother who abandoned her wrong. Both are driven by the need to be admired, to redefine themselves on their own terms at any cost.

There’s a lot of screaming and anger. In my book and this movie, we watch a gradual unraveling as the girls transform and transgress, and they revel in discomfort. By the end, they’re both covered in blood.

I almost want to leave it here and not talk about the differences.

But Pearl and Laure aren’t the same either. Pearl can’t dance to save her life. Laure doesn’t abuse disabled people in her care or kill small animals. I Feed Her to the Beast isn’t really a slasher. Pearl doesn’t have magic. Laure’s ending is somewhat happy. Pearl’s is…what it is. Anything more and I risk spoiling them both.

Monsters feel like home for me, and many others, because they are extreme forms of catharsis, but the feeling isn’t limited to monsters. Look at the survival of the Haywood siblings in Nope, whatever Amy Dunne was doing in Gone Girl, Villanelle in Killing Eve (excluding the last 10 minutes of the series finale), Thomasin living deliciously in The Witch, the android Ava killing her maker in Ex Machina, Benji and his whole crew in Hell Followed With Us, Jade Daniels, my favorite final girl, in My Heart is a Chainsaw.

Just as Pearl and Barbie —transformations born of anger or grief—can feel like a warm blanket and a mug of hot tea on a rainy evening, I want I Feed Her to the Beast to evoke the same. I want some teenager in heavy makeup and an attitude problem to see Laure sink her teeth into someone and think, “Mood” or “girl dinner,” and breathe a little bit easier. To feel like they’ve come home too.

Get your copy of I Feed Her to the Beast and the Beast Is Me by Jamison Shea here.