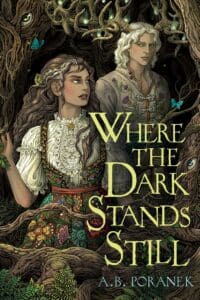

A. B. Poranek on the inspiration behind her debut novel Where the Dark Stands Still

"These were the things I had originally shied away from writing about, and now I embraced wholeheartedly."

This post was written by A. B. Poranek, author of Where the Dark Stands Still.

Several years ago, recovering from a six-year-long reading slump, I picked up the book Uprooted by Naomi Novik. I had bought it from the bookstore, not even looking at the synopsis, based only on one fact: the main character’s name was Agnieszka. An undeniably, utterly Polish name. When I saw it, I was stunned. I remember thinking: books like this can be published? Books that reference Polish food, historical Polish clothing, and draw on Polish myths, could find a home – and popularity – in traditional publishing? As a Polish girl who had grown up in Canada, who had never really thought much about my heritage before, this was my first spark. It would be years until it blossomed into a flame, but from that moment on, I began to look at my upbringing – the stories, the myths, the foods – in a different light.

This was a few years before the boom in folklore and mythology inspired books. With books like Wolf & the Woodsman, Spin the Dawn, Bear & the Nightingale, and Children of Blood and Bone, I saw that there was a place for the sharing of stories inspired by different mythologies, and set out to write one of my own, a YA that would pay homage to the fairytales I had grown up with. And I did write that book. I wrote it, but the final product was a lukewarm, bland and discordantly cutesy book. It drew on Slavic myths, and some Polish folklore, but vaguely. And in the end, I didn’t like it. Something was off. The idea was there, but the heart was missing.

I shelved the book. I wrote another. Shelved that one too. And then finally, one day, sitting in a pit of my own writerly despair, it hit me. I opened the group chat I have with my beloved critique partners, and texted: “what if I revisit that first book? But what if I made it a horror?” and immediately began to re-write that first-ever project.

I realized, soon, why I had never cared much for that first version: it wasn’t Polish enough. Yes, I had drawn a bit on Slavic myths, but there had been an element of hesitance to it, a fear of alienating my audience. But this time, I was going to write the most Polish book possible. So I threw myself into research: scrounging up papers written by Polish ethnographers and historians, visiting museums, and questioning my own grandparents on their lives in the Polish countryside. What I found was a fascinating intersection between Slavic myth, Polish folklore, and traditional food and dress that were documented in the late 19th and early 20th century Poland, but could be traced all the way to Poland’s pagan times.

View this post on Instagram

I learned about superstition: how red ribbons were once tied around young children’s hands to protect against evil – now, they’re seen in Polish folk outfits, often around a young girl’s braids. How Polish peasants in the 17th century would bury their dead with sickles over their throats to ensure that if they rose again as a Slavic monster called strzyga, they would slit their throats on the way out of the grave. Even the famous rowan tree that is so prevalent in well-known Polish songs was once considered protective against evil and demons.

These are the stories at the heart of Where the Dark Stands Still. The final version of the novel draws on three primary elements. First, Slavic mythology, including famous monsters like rusałka and strzygoń (the male equivalent of strzyga) and of course everyone’s favorite famous protector of woodlands, Leszy. Eastern European folktales: the fern flower myth is the main story I drew on (it was my favorite Polish fairytale growing up!), but readers familiar with mythology might also spot homages to others, like the Wawel dragon and the Glass Mountain. Even the Polish white eagle makes a cameo. And thirdly, Polish culture. From bigos to traditional folk clothing to a warm zapiecek, so many of the little things I had taken for granted growing up suddenly took on new significance for me – and I truly hoped I could bring a little awareness to them by featuring them in this novel.

I’ll be honest, not everything in WTDSS is historically or mythologically accurate – I took plenty of liberties for the sake of storytelling or simplicity, and altered the origins of some myths to fit the story. But doing the research I had, I was able to make these decisions consciously, to know what to include and what I could change. There are also smaller things that I consider very Polish, that aren’t linked to folklore – a profound love of forests, an ability to live off the land, and an impressive degree of stubbornness exemplified in different ways by both of WTDSS’ protagonists. These were the things I had originally shied away from writing about, and now I embraced wholeheartedly.

I am so deeply proud of this novel, and of just how much Polishness I managed to sneak into Liska and the Leszy’s story. Yes, WTDSS draws on the horror elements of Slavic mythology, but many people have remarked that there is a cozy element to it as well, and I think that element emerged accidentally from my desire to include little things I loved about Poland’s traditions: the cooking, the lifestyle, the stories.

And so, to those who are discovering Polish mythology and culture for the first time, I hope WTDSS is an adventure. And to those who are Polish, even in part, I hope more than anything that this novel feels like a homecoming.

Get your copy of Where the Dark Stands Sill by A. B. Poranek here.

Get your copy of Where the Dark Stands Sill by A. B. Poranek here.